A data story from women in a semiarid region of Brazil

*This story was written by the following women: Ducicleide Maria da Silva, Gigliola Silva Araújo, Ianka Sayonara da Silva, Josefa Ferreira da Silva, Maria do Carmo da Conceição Carvalho, Maria Karoline Policarpo Silva, Manuella Donato, Mariana de Albuquerque Vilarim and Thalya Carla Vieira de Lima and Patricia Maria Chaves . It was translated by Sonia Jay Wright.*

Contextualizing the Research

The below covers and details the project Leveraging the 2030 Agenda to Strengthen Women’s Land Rights, carried out and coordinated by Espaço Feminista (EF) a Brazilian feminist CSO dedicated to the economic and political empowerment of women.

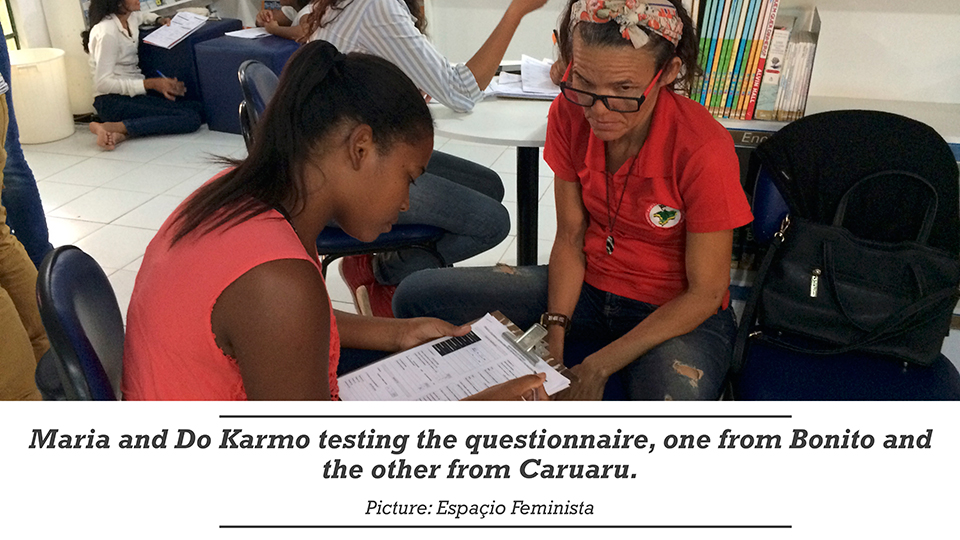

Giving attention to both rural and urban spaces, the nuances of each, as well as the relationship between these spaces, the project focused specifically on the intersections between land and gender. We worked in the diverse zones and districts of both Bonito and Caruaru, two municipalities of the semiarid region of Pernambuco, Brazil. In order to develop our research in its’ first phase, questionnaires were administered in both municipalities. Women leaders from local social movements, most of which are members of EF, or who had already engaged in EF’s activities in some capacity, were invited to take part in that process. They first engaged in dialogue on how they perceived gender issues in their municipalities, interacting with researchers allowing a horizontal capacity building process prior to the collection of data.

After the very initial days of research, EF’s team was able to get a better understanding of the local reality. Four hundred and sixty-nine questionnaires were conducted and applied over a period of two weeks, which resulted in a rich database and basis for the project.

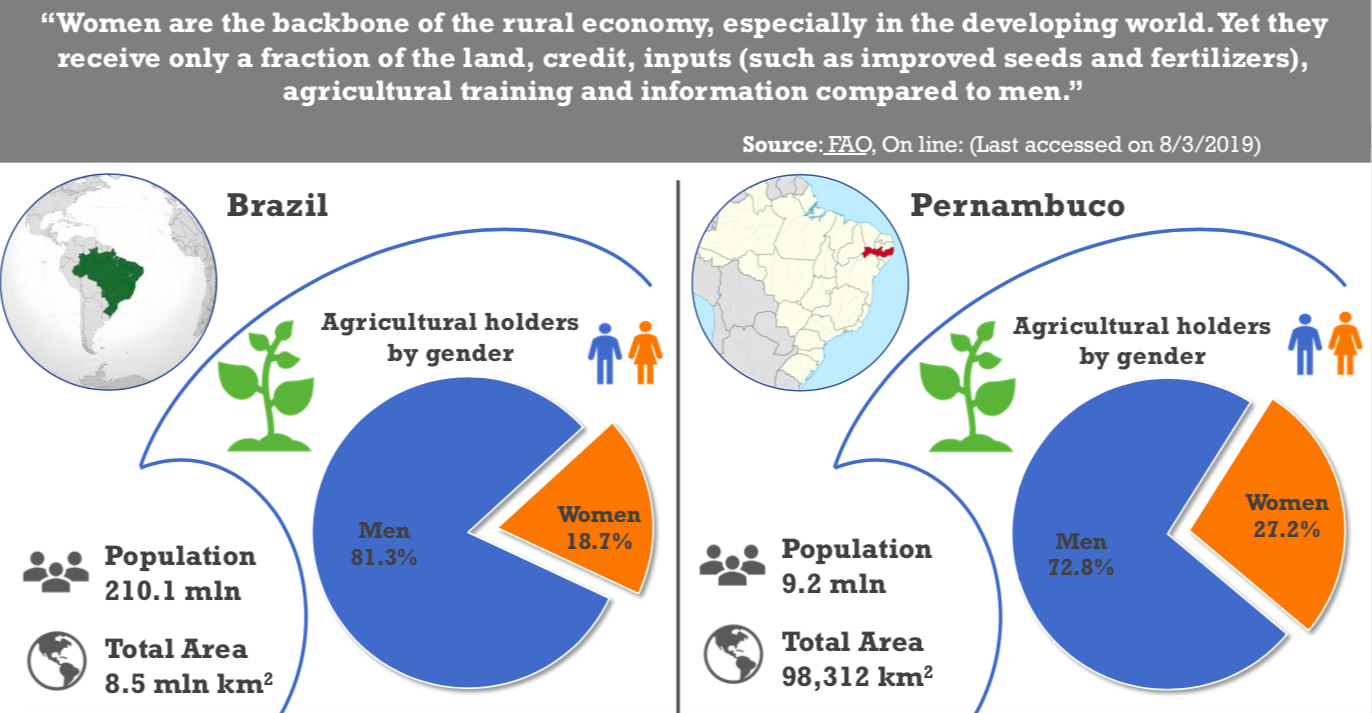

The fieldwork, as well as the review of the official data (from IBGE, the National Statistic Office), served as the basis for a series of discussions with grassroots women. These women expressed how touched they were by the home visit discussions, which reflected the fact that an immense amount of land remains concentrated in the hands of a very select group of people, white males being the majority. The group also began to reflect on the grave contradictions and this process was a great opportunity to further discuss the gender relations of power. Some such example were the prevalence of domestic violence in some communities, as well as the fact that women have often never held documents for their land or housing.

Sources: Quote - FAO/Farming First, On line: (Last accessed on 8/3/2019); Data - Brazil Agricultural Census 2017 – Preliminary Results, on line (Last accessed on 8/3/2019)

Women’s Perceptions

Using a methodology oriented towards a process of exchange of knowledge and experiences that could engender a pathway to women’s empowerment, Espaço Feminista facilitated meetings in both Caruaru and Bonito, to discuss the issues related to the research.

Linking previous theoretical and empirical knowledge, with experiences provided by the project, the women started discussing the issues which they considered to be relevant, highlighting issues related to women’s land rights, domestic violence, as well as racial issues.

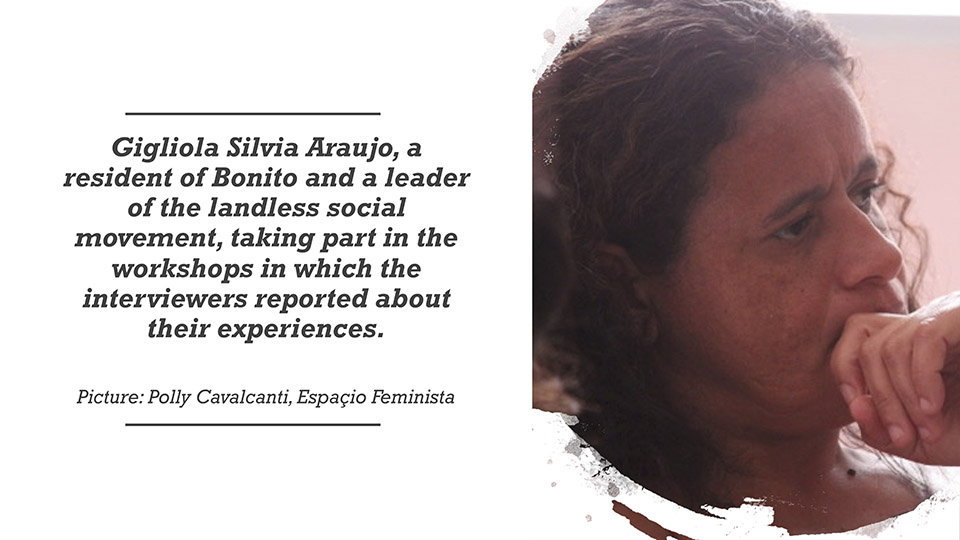

Gigliola Araújo, a resident of Bonito and a leader of the landless social movement, highlighted the urgent need to approach issues related to land and gender. She observed that women are frequently denied their rights. She said: “They never have any rights (to the land). They never say that they will have the land in their name; the land is always in their husband or brother’s name. (…) We thought that as time evolved, people would also evolve. But in fact, only the wealthy have evolved, because the poor are in the same conditions and in the same situation.”

Gigliola also later affirmed that it is very usual to find families who live on a plot of land for decades without having any documents that prove their land ownership. She adds that: “In many cases, all they have is a tax certificate”. A similar situation occurred in Caruaru, where surveyor Thalya Lima affirmed that many of the people who she had encountered had lived in the same house forever. Another relevant remark was that many surveyors had observed that women mentioned having land certificates, but in fact and reality they didn’t. This was because they feared that the survey was related to a governmental action that could claim the land ownership.

The racial issue, also emerged as a recurrent one during the debates. Many of the respondents had difficulties identifying their own race. Black women, for example, do not recognized themselves as such, declaring that they were white or brown. In Brazil, due to structural racism and racist society, to be black, many times infers to be the subject to an inferior position, as portrayed by Ducicleide da Silva, one of the respondents: “I do not consider myself black, have you seen a black woman with green eyes?"

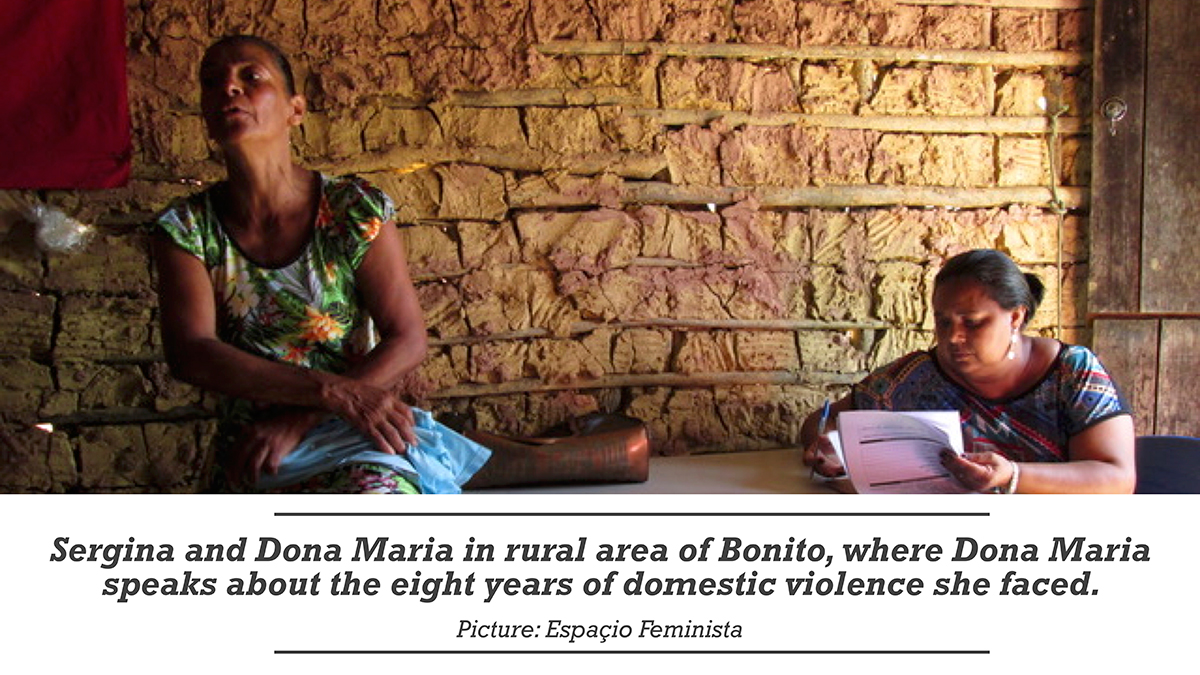

The issue that called the most attention was that of domestic violence. Karoline da Silva, a surveyor from Bonito, reported that she realized that the local situation had grown worse. According to her, there was a general disbelief and lack of knowledge from the women who were victims of domestic violence, about the protection the state could ensure to them. This perception was discussed during one of her interviews. She expressed that if she reported her husband’s abuse, he would be arrested for a few days, and soon after released, when she would fear for her life. During the group discussions the link between land tenure security and domestic violence was explored. Many women affirmed that if they had the land in their name, they could have had another life. There is a strong link between land tenure security and domestic violence that EF is still investigating.

Domestic violence, while being endemic in some communities such as Bem-te-vi, situated in the rural area of Bonito, is a fact that is vehemently denied by many women. While women may deny because of fear or shame, men, on the other hand, preferred to put forth that there was no such domestic violence in their communities, contributing to the widely accepted notion that physical or emotional violence against their partners was intrinsic to their relationship. Ianka da Silva another surveyor from Caruaru, for example, mentioned that one of her male interviewees told her that if she were married, she would realize that domestic violence happens on a daily basis, just in different manners.

The development of EF’s own database gains other shapes as far as the interviewed tell their stories and the interviewers seize other realities, observing, empirically and theoretically, the local disparities fed many times by machismo, misogyny and racism, as well as, by social class relationships.

Processes that Empower

The possibility of building a process of systematization of the local knowledge based on the experiences and perceptions of the communities gradually, allowed the researchers to better connect their local realities with structural issues. As leaders of said communities, the data works as a crucial tool to support their demands and so they can be heard and their knowledge recognized by institutional powers.

Direct and primary action-research which feeds into an expanding knowledge-base, allowed local leaders to feel more empowered to claim and advocate for specific public policies within their communities. In Bonito, the issue of domestic violence was very evident, whereas in Caruaru for example, one of the main issues presented in women’s interviews was the lack of access to water (including drinking water).

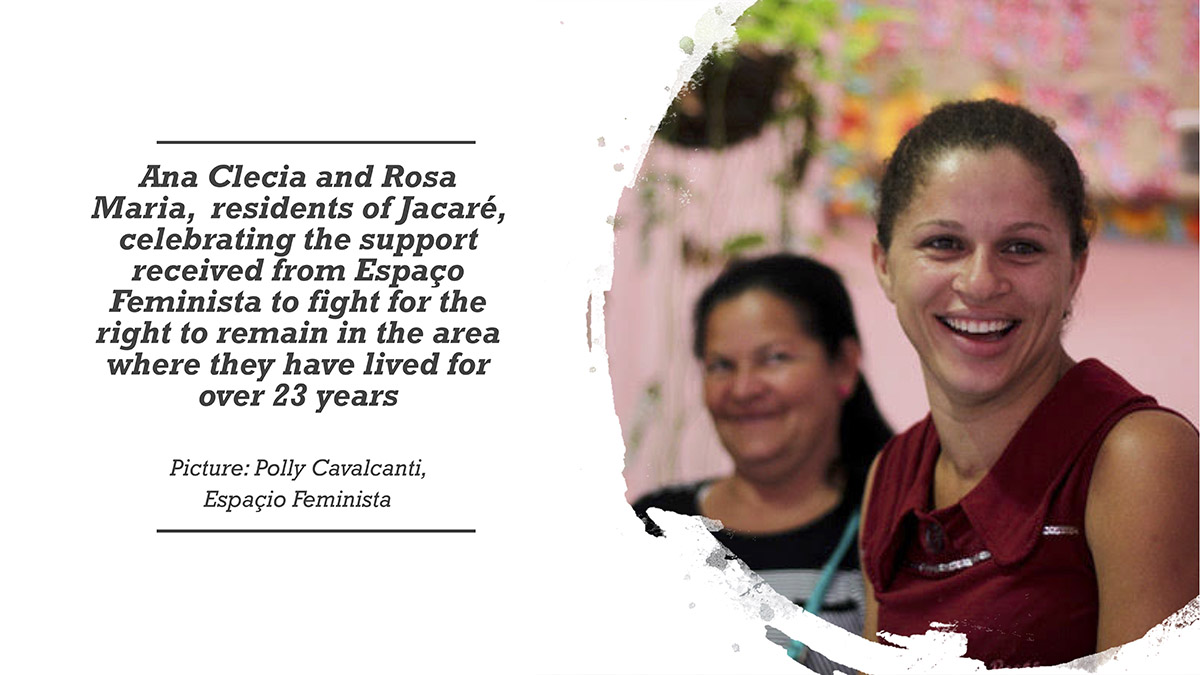

In both municipalities, the inequality in terms of women’s land tenure security was gravely exposed. Thus, the urgencies identified were immediately dealt with by government agencies responsible for such policies, both at a local and state levels. On a similar note, the experience and knowledge generated by this research have helped to orient the next steps of the Project. In the case of the community of Jacaré, identified by Dona Silvia (Josefa da Silva), interviewer from Caruaru, the residents are facing constantly threat of eviction due to real estate advances. Thus, the EF team made several visits to the area, established consistent dialogue with residents and began a request for land regularization within the local government. Therefore, the whole process of building the research and working from the data based on the local knowledge have contributed meaningfully to strengthen the capacities of the women directly involved in the project and to create strategies to collectively empower themselves and their communities based on diverse forms of knowledge.

Proportion of countries where the legal framework (including customary law) guarantees women’s equal rights to land ownership and/or control

Last updated on 1 February 2022

This indicator is currently classified as Tier II. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) is the main Custodian agency. UN Women and the World Bank are partner agencies.

(a) Proportion of total agricultural population with ownership or secure rights over agricultural land, by sex; (b) share of women among owners or rights-bearers of agricultural land, by type of tenure

Last updated on 1 February 2022